Polar Bears, Politics, and Apocalypse

The 3 big problems in climate communication and how to fix them.

by Abel Gustafson and Matthew Goldberg

October 2023

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues of our time, but we have been slow to address it. This inaction is not due to a lack of scientific knowledge or technological solutions. We have plenty of both. What we truly lack is sufficient motivation and priority among everyday people and their elected government officials. The primary problems to solve are in communication and public opinion. In short, the front lines of this issue are the hearts and minds of everyday people.

But people and organizations are not naturally skilled at talking about climate change. Despite good efforts and good intentions, there are three common patterns of climate communication that are actually quite counterproductive.

Polar Bears

In one study, a survey of Americans asked “what is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the term ‘global warming?’” The most common answers were things like “melting ice” and “polar bears.” This makes sense, because polar bears, penguins, and melting sea ice are the standard imagery for climate change. But this reveals the roots of a significant problem.

The problem with this is that most people do not naturally care deeply about melting ice or polar bears. We humans evolved to prioritize immediate dangers that we can see and feel right now. Climate change is the exact opposite. It is often invisible, abstract, slow-moving, and seems distant in time and space. This is the perfect storm in the psychology of persuasion—creating huge challenges when trying to motivate people to pay attention, to care deeply, or to take action.

When we emphasize distant effects (e.g., polar bears, melting sea ice) or abstract phenomena (e.g., parts per million of atmospheric CO2), we create a large distance between the bad effects and the audience. We say, in essence, “this is a problem for polar bears.” We fail to connect the issue to anything that is truly important to the average person.

Fortunately, there are clear solutions. Our analyses show it can be very effective to emphasize the ways that climate change is affecting everyday people, right here, right now. In one recent study, we show that when people hear personal stories of these climate effects, this creates a stronger understanding of the risks. The data show that a likely reason why personal stories can be so effective is because they activate concern and compassion, and also because they bring the issue closer to home.

Politics

It’s no secret that climate change is a politically polarized issue in the United States. But our recent research shows that people overestimate the actual degree of political polarization. That is, people think that we are more divided than we actually are. This can lead people to avoid the issue altogether, and to think it is taboo or socially risky to express their own worries about the issue.

Part of the reason Americans tend to assume there is a radical division on climate change is because the issue is commonly portrayed as being a political battle. It is typical for news stories to focus on political struggle between opposing groups. This causes people to think of the issue as being mostly a matter of “us versus them.” Focusing on politics—or even using politically-charged buzzwords—causes people to put up their defenses against “the other team.” This defuses any efforts to work together.

To combat this tribalism, we need narratives that focus on common goals and shared values. For example, we can point to ethics we all learned as children, such as “leave it better than you found it.” We can appeal to innate motives for tangible benefits like clean air and clean water. We can also frame the issue as being about protecting innocent people from harm. Our recent research

has shown that one of the leading motives for protecting nature—shared by people across the world—is to maintain the balance of Earth’s delicate system. That is, many people already have a mental image of nature being like a Jenga tower. They know we should not tinker with the blocks. These universal narratives are key for reducing polarization and building commonality.

We find convincing evidence of the effectiveness of appealing to the values of the audience, such as in our research on a large-scale ad campaign designed to persuade Republicans about the reality and severity of climate change. In this campaign, the ads featured short video interviews with a Christian climate scientist, an Air Force general, and two Republican political figures. Each person discussed how climate action aligns with their values, such as Christian teachings, national security, and conservative politics. After deploying these video ads on Youtube and Facebook in two target cities, we found that the campaign had a substantial positive effect on Republicans’ climate opinions after just 30 days. This shows we can have large effects in the real world when we find ways to resonate with the values of the target audience.

Apocalypse

In 2021, researchers conducted a survey of youth (ages 16-25) in 10 diverse countries. They found that a majority of youth felt “powerless” regarding climate change and only 31% felt “optimistic.” When asked if “Humanity is doomed,” more than half (56%) said yes.

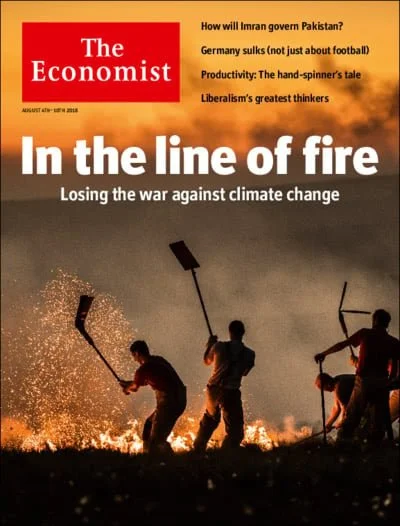

This prevalent feeling of doom and hopelessness is (you get the theme) an effect of how we have been portraying climate change. It is common to crank the fear up to “11” with the assumption that more fear will produce more persuasion and more action. We often see dark, apocalyptic portrayals of a scorched Earth, along with dramatic rhetoric about human extinction.

But all this fear can be counterproductive. When people feel too much fear, they try to alleviate their discomfort by ignoring the problem, changing the channel, or finding reasons to discredit it. This is a “flight” response that occurs when feeling incapable of dealing with the danger.

Our research shows a proven strategy for overcoming this. It centers on supplementing the fear with a large dose of hope. Specifically, we need to include four key ingredients:

Threat Severity: This problem is severe. It will have very harmful effects.

Threat Salience: This problem is relevant to you personally. It will affect you.

Self Efficacy: You are capable of taking action! You have the ability to affect the solution.

Response Efficacy: This solution is effective! It can successfully reduce the threat.

When fear-based communication emphasizes threat (the danger is severe and relevant) and nothing else, people respond in counterproductive ways—such as burying their head in the sand. But when we also provide clear information about efficacy (the ability to solve the problem), then people become more motivated and willing to face the threat and take action to defeat it.

This makes sense. Who would take action when they have been convinced it is pointless? People need to feel empowered and hopeful. Overall, this means that—in addition to emphasizing the danger—we also need to present solutions that are doable and effective.

Summary

Climate communication has good intentions but bad habits. In this paper, we have discussed 3 common habits that are actually counterproductive. Repeatedly, climate communication has:

Focused on imagery that portrays the problem as far away and irrelevant to our lives.

Reinforced the “us vs them” mentality, making it feel toxic to even talk about the issue.

Preached the fire and brimstone of an apocalyptic future with no way out.

Given all of this, it’s really no surprise when the data show us that many Americans feel climate change is either a) far away and irrelevant to them, b) too controversial to get involved in, or c) a lost cause because it’s already too late.

But we can fix this! These perceptions were created by communication patterns, and they can be changed the same way. When we change our narratives, we reshape the way that people respond. Throughout this article, we have provided practical strategies for communicating more effectively. These can be easily done by individuals in everyday conversations, as well as by organizations in large-scale campaigns. This requires strategy, care, and effort. We believe it’s worth it.

Cite this

Gustafson, A. & Goldberg, M. H. (2023). Polar Bears, Politics, and Apocalypse: 3 big problems in climate change communication and how to fix them. XandY. New Haven, CT. Retrieved from: https://www.xandyanalytics.com/3-problems-in-climate-communication